Here we go again: A Public-Facing Vulnerability in Palo Alto Networks Firewalls

A recent vulnerability in Palo Alto Networks firewall devices raises concerns about the security of public-facing services like VPNs.

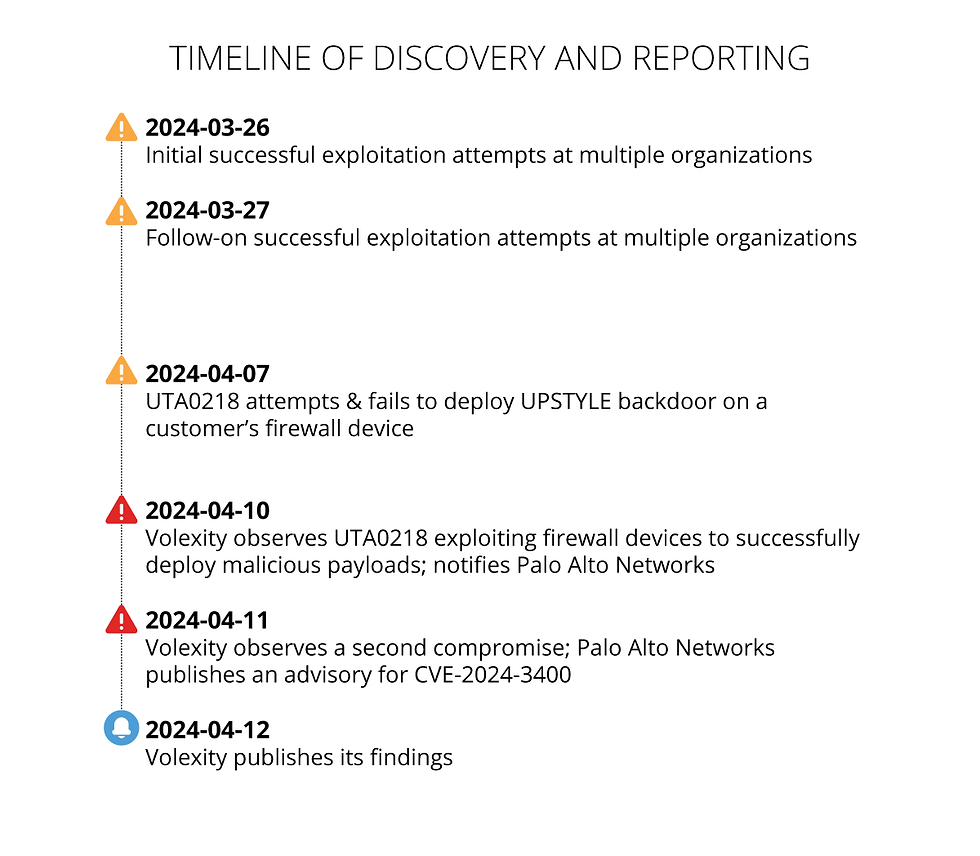

The latest vulnerability is tracked as CVE-2024-3400 and has been secretly exploited in the wild for at least a month, and possibly even longer. These devices have effectively become open doors on the internet, allowing unauthenticated attackers to execute arbitrary code with root privileges. Patches are still due to be released.

However, before bashing Palo Alto Networks, it’s worth remembering this is a recurring pattern affecting all vendors at one time or another, whether it’s Microsoft, Cisco, Fortinet, Ivanti, etc. In fact, this is not about the vendor at all, but rather about the business model where devices are installed and managed independently of the vendor – essentially the way we’re used to operate equipment for the last few decades or so.

However, this approach clashes with the evolving threat landscape in several ways:

When a public service like VPN operates as-a-service (SaaS) within the vendor’s data center (as opposed to the self-hosted approach), the vendor can react much faster and proactively block threats by implementing workarounds even before official patches. That seems to be the case this time as well - in its advisory Palo Alto Networks says: "Cloud NGFW, […] and Prisma Access are not impacted by this vulnerability." Also, "while Cloud NGFW firewalls are not impacted, specific PAN-OS versions and distinct feature configurations of firewall VMs deployed and managed by customers in the cloud are impacted."

Developing patches is a huge effort for the vendor, extensive QA and release cycles limit the agility of the vendor to quickly fix bugs and test solutions across its customer base. Patches typically require weeks to land on customer premises, while at least half of the device “population” will be left unpatched for months to come, creating a huge vulnerability that's difficult for the vendor to control.

Even after patching, identifying compromised devices requires extensive resources and expertise beyond many organizations' capabilities. Hunting for threats requires investments in SIEM, SOAR, XDR and other SOC technologies, not to mention employee expertise. In this case, attackers have been observed to leverage the Active Directory credentials commonly found in firewalls to integrate with the on-premise infrastructure. Detecting traces of infiltration across the Active Directory domain requires a significant and costly threat-hunting effort, long after patches have been deployed.

Having this in mind, any risk management strategy should consider deployment models such as SASE, which delegates public-facing remote access services to the vendor, operated as a service and primarily delivered as a cloud service to customers. This approach enhances security and reduces the burden on individual organizations.